Sailing Terms You Should Know Before Your Next Journey

Table of Contents

- Sailing through time: Historical sailing terms and their origins

- From Deck to Dock: Exploring Essential Sailing Gear

- Key sailing terms

- Understanding nautical weather terms

- Decoding navigation and compass terms

- Sailor’s knot-tying guide: Essential knots for the open sea

- The galley and beyond: Living on board a sailboat

- Knots Per Hour: The language of speed and distance at sea

- The Language of sailing safety

To truly immerse yourself in the world of sailing, it's essential to know the language, so you can confidently navigate both the waters and the terminology. The language of sailing is deeply rooted in tradition, with many of the terms we use today having been passed down by sailors for hundreds of years. By learning this vocabulary, you’re not just acquiring technical knowledge—you’re becoming part of a timeless maritime legacy. For many newcomers, sailing can feel intimidating, shrouded in a world of complex jargon, unwritten rules, and centuries-old conventions. However, once you start to understand the terminology, the seemingly cryptic language of the sea begins to reveal itself, and what was once forbidding becomes fascinating.

Sailing through time: Historical sailing terms and their origins

Port and Starboard - These two terms are essential for understanding directions on a boat, but have you ever wondered why sailors use them instead of just saying "left" and "right"? The word "starboard" comes from the Old English term steorbord, meaning the side of the ship on which it was steered—typically on the right side. The term "port" was adopted later to refer to the left side, where the ship would dock, or "port." Even today, these terms prevent confusion in navigation, especially when directions need to stay consistent regardless of which way you're facing.

Logbook - Have you heard of a ship’s "logbook"? This term dates back to when sailors used an actual log—a piece of wood tied to a rope with knots in it—to measure the ship’s speed. They would toss the log overboard and count how many knots passed through their hands in a certain period of time, giving rise to the term "knots" for speed. The information was then written down in a "logbook." Modern sailors still use logbooks to record important details of their journeys, although now they rely on advanced technology instead of floating logs.

Fathom - The word "fathom" has an ancient history and was originally a term for the span of a man’s outstretched arms—about six feet. Sailors used it as a unit of measurement for the depth of water. Over time, it also became a term meaning to understand something deeply. Even today, both meanings are still in use. If someone says they can’t "fathom" a concept, it’s almost like they’re saying they can’t measure or grasp it completely.

"Toe the Line"

This term comes from an old naval practice. On British Royal Navy ships, sailors had to stand at attention with their toes perfectly aligned with the seams of the deck planks during inspections. If someone wasn’t standing in a straight line, they were disciplined. Hence, "toe the line" evolved into a phrase meaning to obey the rules or conform to expectations, keeping your behavior in check just like the sailors of old.

From Deck to Dock: Exploring Essential Sailing Gear

Sailing is such an exciting adventure, but one has to be well-equipped in order to make the adventure safe as well as enjoyable. Be it deck or dock, the importance of essential gear is vital. On board, one needs non-slippery deck shoes, gloves for handling ropes, and a life jacket that would keep him alive if bad weather suddenly turns up. Navigation tools like a reliable compass and GPS will help plot courses and enable one to avoid hazards. Weather-specific clothing, waterproof jackets, and thermal layers are comforts for all eventualities. Fenders on the side of the boat prevent damage when against a dock, and proper mooring lines tie it up safely. With the proper equipment, any sailor is prepared against the hostility of the sea.

The language of anchoring

Anchoring is one of the most fundamental skills every sailor must master. However, understanding the vocabulary of anchoring can feel like navigating through uncharted waters for beginners. From different types of anchors to the specialized terms used when dropping and securing them, here's a guide to the language of anchoring.

Types of Anchors - Anchors come in many shapes and sizes, each designed for specific conditions. Two of the most commonly used are the fluke anchor and the plow anchor:

Fluke anchor (or danforth anchor): Known for its lightweight and strong holding power, the fluke anchor has two large flat “flukes” that dig into the seabed. It’s ideal for coastal cruising and is easy to stow when not in use.

Plow anchor: As the name suggests, this anchor resembles a farmer’s plow and is great for penetrating a variety of seabeds, including sand, mud, and rocky bottoms. Its curved design helps it reset itself if the wind or current shifts the boat’s position, making it a versatile choice for many sailors.

While dropping anchor may seem straightforward, there’s a whole lexicon associated with this essential activity. Here are some key terms to know:

Weigh anchor - This phrase refers to the action of lifting the anchor from the seabed and preparing to sail. "Weighing anchor" is often the first step when setting off on a new voyage, signaling that the boat is ready to move.

Anchor rode: The rode is the line, cable, or chain that connects the anchor to the boat. It’s crucial to have the right length and material for the type of seabed and conditions. A mix of chain and rope is often used, with chain providing additional weight and holding power, while rope adds flexibility.

Scope: This refers to the ratio of the length of the rode to the depth of the water. For safe anchoring, a scope ratio of 5:1 or 7:1 is typically recommended, meaning you should have five to seven times the length of the water depth in rode to ensure the anchor is securely set.

Hawsepipe: The hawsepipe is the hole in the bow of the boat through which the anchor rode passes. It protects the boat’s hull and allows the rode to run smoothly when raising or lowering the anchor.

Drag: If the anchor is not properly set or the conditions change, the boat may start to drift. This movement is called drag, and it’s important to monitor for any signs that the anchor is slipping across the seabed instead of holding firm.

Anchoring techniques: Understanding these terms is essential, but applying them correctly ensures safe and effective anchoring. For instance, when dropping anchor, you’ll want to make sure to release enough rode for the scope you need, ensuring the anchor has enough line to dig in and hold securely. Using a combination of chain and rope helps prevent the boat from tugging directly on the anchor, which could cause it to break free.

Always remember to check for anchor drag by observing landmarks or using electronic instruments to track the boat’s position relative to the anchor point. If you notice the boat shifting, you may need to "weigh anchor" and reposition it for a more secure hold.

Sail Shapes and their functions

One of the most fascinating aspects of sailing is the way different sails harness the wind to propel a boat forward. Each sail has a specific purpose and functions best under certain wind conditions. Understanding these sail types and how they work will allow you to adjust to the ever-changing forces of the wind with confidence and precision.

Here’s a breakdown of the most commonly used sails and how they catch the wind:

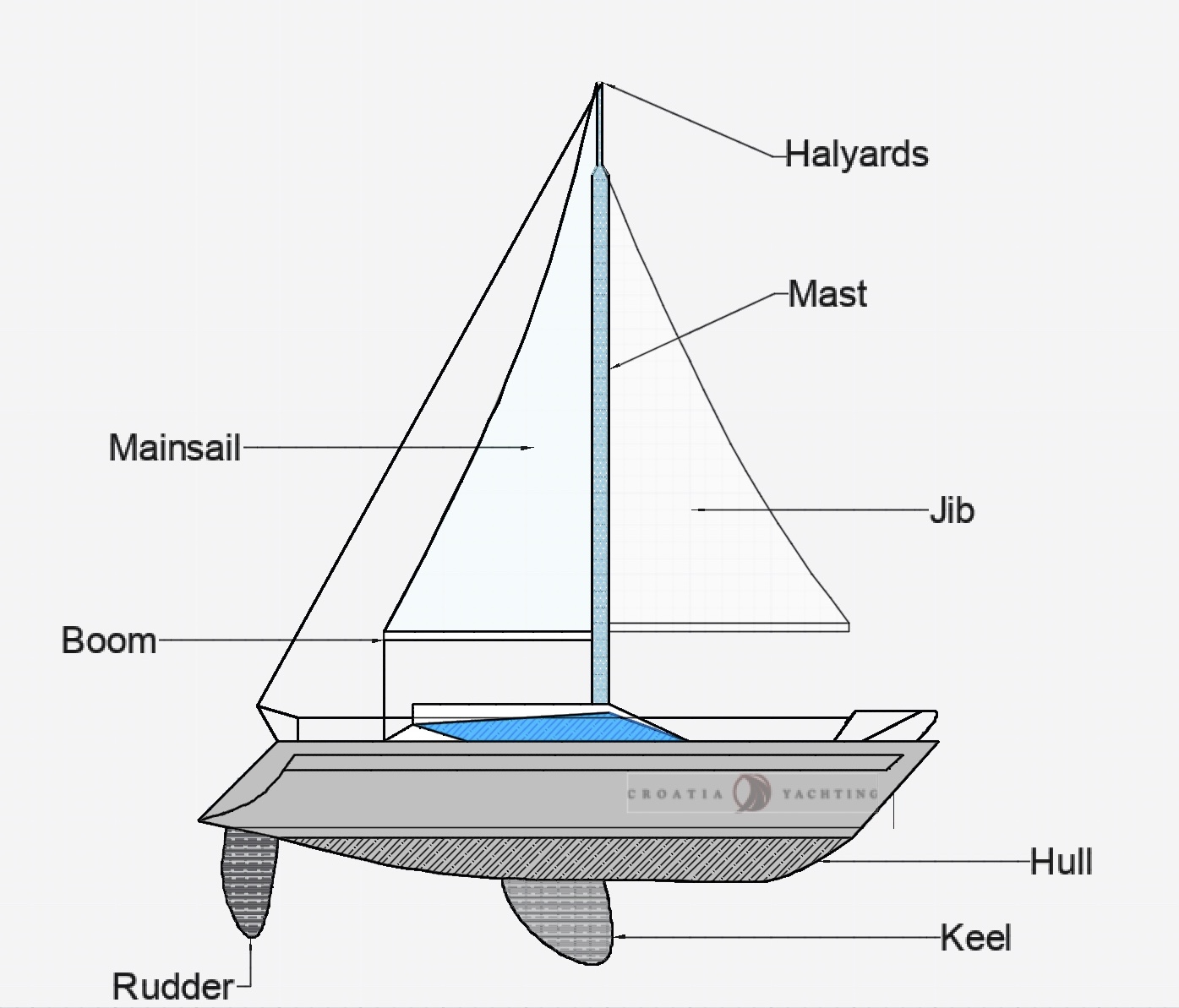

Mainsail

The mainsail is the primary and largest sail on most boats. Attached to the mast and boom, it’s the workhorse of the sail plan, providing the majority of the propulsion. The mainsail is used in almost all wind conditions, from light breezes to heavy gusts. When the wind picks up, you may need to "reef" the mainsail, which means reducing its size by folding part of it down to make the boat easier to control. The mainsail's powerful shape and position allow it to act as the backbone of your sail configuration.

Jib

The jib is a smaller sail located at the front of the boat, attached to the forestay, a wire running from the top of the mast to the bow. The jib works in tandem with the mainsail, helping to balance the boat and increase speed by funneling wind across the mainsail. Jibs are especially effective when sailing upwind (toward the wind) and allow for tighter, more precise steering. Unlike the mainsail, the jib is controlled by sheets (ropes) running to winches on either side of the boat.

Genoa

The genoa is similar to the jib but significantly larger, often extending past the mast. This extra surface area makes the genoa more powerful than the standard jib, particularly in light winds. However, because of its size, it can become difficult to handle in stronger winds, and sailors may need to "reef" the genoa or switch back to a smaller jib when the breeze strengthens. The genoa excels in reaching (when the wind is coming from the side) and broad reaching (when the wind is at an angle from behind).

Spinnaker

The spinnaker is the colorful, balloon-like sail that’s often seen billowing out in front of racing boats.

This sail is designed for downwind sailing, when the wind is coming from directly behind or at a broad angle. The spinnaker catches large amounts of wind, giving the boat a significant speed boost. It’s a light, delicate sail and is typically only used in lighter wind conditions, as it can become difficult to control in heavy weather.

There are two types of spinnakers: symmetrical and asymmetrical. Symmetrical spinnakers are used on traditional rigs, while asymmetrical spinnakers are more versatile and easier to handle, especially on modern boats.

The other parts of the sailboat include:

| Hull | Supports the rigging and is carrying the passengers. |

| Keel | Keeps the boat from sliding sideways and is attached to the hill. |

| Rudder |

Used for steering the sailboat. |

Key sailing terms

To effectively manage these sails and adjust to changing wind conditions, sailors must also be familiar with essential terms that describe how sails behave:

Reefing: As mentioned earlier, reefing refers to reducing the size of a sail when the wind is too strong. This can be done by partially lowering the sail and securing the excess fabric. Reefing keeps the boat more stable and prevents excessive heeling (tilting).

Luffing: When a sail is not properly trimmed (adjusted) for the wind direction, it may start "luffing." This means the sail flaps and loses its shape because the wind isn’t filling it properly. Luffing typically occurs when sailing too close to the wind, and the solution is to either adjust the sail or change direction slightly to capture the wind more efficiently.

Sheeting: Sheeting refers to adjusting the angle of the sail to the wind using ropes called sheets. Proper sheeting is key to keeping the sails tight and the boat moving at optimal speed.

Trimming: Trimming is the process of fine-tuning the sails to make the most of the wind. A well-trimmed sail maximizes speed and control, whether you’re sailing upwind or downwind.

Understanding nautical weather terms

Understanding nautical weather terminology not only keeps you safe but also helps you make informed decisions when you're navigating ever-changing conditions. Let’s break down some of the key weather terms every sailor needs to know.

Gale

A gale is a strong wind that usually ranges between 34 to 40 knots (39 to 46 mph). Gales can be highly dangerous, especially for small boats, as they can create large waves and rough seas. Sailing in a gale requires advanced seamanship and a well-prepared vessel. Gale warnings are issued by weather services when such conditions are expected, and it's usually best to avoid sailing when a gale is forecasted.

Squall

A squall is a sudden, intense burst of wind, often accompanied by rain or thunderstorms. Squalls can develop quickly and unexpectedly, causing rapid changes in wind direction and speed. For sailors, it’s important to watch the horizon and sky for signs of squalls, which can turn a calm sea into a challenging environment in a matter of minutes. Being prepared to reef your sails quickly is essential when a squall hits.

Windward and Leeward

These two terms are fundamental to understanding wind direction on a boat:

Windward: This refers to the side of the boat or object that faces into the wind. When you are sailing windward, you are moving towards the source of the wind. Sailing windward requires a lot of skill as you need to navigate with the sails closely trimmed to maintain speed and control.

Leeward: Conversely, leeward is the side of the boat that is sheltered from the wind. When you are on the leeward side, the wind is blowing over the boat and away from you. Understanding leeward and windward helps in positioning your boat correctly for maneuvering and safety, especially when dealing with strong winds or stormy conditions.

Decoding navigation and compass terms

Understanding navigation and compass terms is essential for planning and following accurate routes, whether you're navigating coastal waters or crossing an ocean. Here’s a breakdown of key terms that help sailors plot their course and stay on track:

Bearing

A bearing is a crucial navigational term that refers to the direction or angle between your current position and another point, measured in degrees clockwise from true north or magnetic north. For example, if an island lies directly east of your current location, its bearing would be 90 degrees. Bearings are used to guide sailors towards specific landmarks, buoys, or waypoints, ensuring the boat stays on the intended course. Bearings can be taken using a compass, GPS, or chart plotter, and they are essential when sailing in unfamiliar waters or during poor visibility.

Dead Reckoning

Dead reckoning is a traditional method of navigation that involves calculating your current position based on a previously known position, your boat’s speed, the direction of travel, and the time elapsed. This method was used by sailors long before GPS or electronic chart plotters became available and is still valuable as a backup. Dead reckoning can be tricky as it doesn’t account for external factors like currents or wind that can push the boat off course, but when used properly, it helps sailors estimate their location and maintain their intended route when other navigation tools aren’t available.

Chart Plotter

A chart plotter is a modern electronic device that combines GPS technology with digital maps to show a boat’s exact position in real-time. Chart plotters can display routes, waypoints, depths, and hazards, making them invaluable for sailors navigating through complex or unfamiliar waters. By plotting a course directly on the electronic chart, sailors can see their progress and adjust as needed to avoid obstacles or stay on the most efficient path. Chart plotters have largely replaced traditional paper charts, but understanding how to use both remains important for safety.

Latitude and Longitude

Latitude and longitude are the two key components of the global coordinate system used to pinpoint exact locations on Earth. Latitude lines run horizontally and measure how far north or south a location is from the Equator, while longitude lines run vertically and measure how far east or west a location is from the Prime Meridian (which passes through Greenwich, England). These coordinates are given in degrees, minutes, and seconds, and they allow sailors to determine their position anywhere in the world. Knowing how to read and interpret latitude and longitude is vital for setting a course, finding waypoints, and communicating your position to others, particularly in emergencies.

Waypoint

A waypoint is a specific location or reference point on a navigational route. It can be a fixed point like a buoy, a GPS coordinate, or a landmark. Sailors use waypoints to break up longer voyages into smaller segments, making it easier to stay on course. When you reach one waypoint, you adjust your heading to aim for the next one, creating a step-by-step guide to reach your destination.

Heading vs. Course

A heading is the direction your boat is currently pointing, while a course is the intended direction you want the boat to travel over the water. The two don’t always match perfectly because factors like wind, current, or waves can cause the boat to drift. By constantly adjusting your heading, you can stay on course, ensuring you reach your destination accurately.

Rhumb Line

A rhumb line is the straight line drawn between two points on a nautical chart. It represents the simplest, most direct path between those points, making it a helpful guide for sailors. However, because the Earth is a sphere, a rhumb line may not always be the shortest distance over long distances; for ocean crossings, sailors may use a great circle route (a curved line) to minimize distance traveled.

Sailor’s knot-tying guide: Essential knots for the open sea

Knots play a vital role in rigging, docking, securing equipment, and ensuring the overall safety of the boat and its crew. Different knots serve specific purposes, and knowing which knot to use in each situation can make all the difference when you’re out on the water. Here’s a guide to some of the most essential knots every sailor should know:

Bowline

The bowline is often called the "king of knots" because of its versatility and reliability. This knot creates a secure loop at the end of a rope that doesn’t slip or come undone under load, yet it can be easily untied even after bearing weight. The bowline is commonly used for securing a line to a post or ring, tying off a sail, or creating a loop to throw to a person in distress. One of the key advantages of the bowline is that it doesn’t jam, making it a perfect knot for critical situations.

Why it’s essential: The bowline is crucial when you need a fixed loop that will not tighten or slip, making it ideal for attaching lines to sails, cleats, or mooring rings.

Cleat hitch

The cleat hitch is one of the most important knots for securing a boat to a dock. This knot involves wrapping a line around a cleat—a T-shaped fitting often found on docks and boats—in a figure-eight pattern, which provides a firm grip while allowing for quick release. The cleat hitch is simple yet effective, ensuring your boat remains securely tied while docked but can be released without fuss when it’s time to depart.

Why it’s essential: A properly tied cleat hitch keeps your boat securely fastened to the dock, even in rough waters, preventing damage or drift. It’s easy to learn and fast to tie, making it a go-to knot when docking.

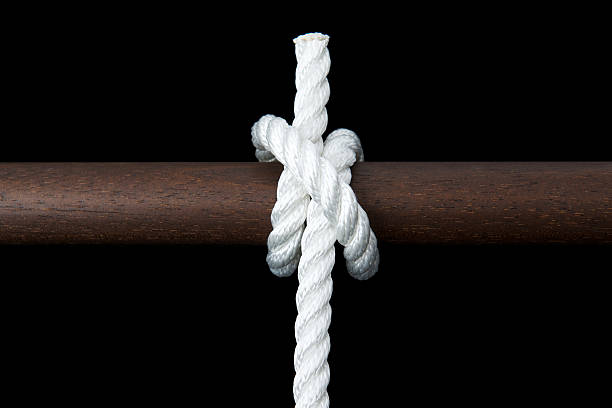

Clove hitch

The clove hitch is another versatile knot used to temporarily secure a line to a post, rail, or spar. It’s particularly useful for tying fenders (protective bumpers) to the side of a boat or securing lines during rigging. While the clove hitch can slip under heavy or jerky loads, it’s excellent for quick tasks that require frequent adjustment, such as tying off a boat for short periods.

Why it’s essential: The clove hitch is a great knot for temporary tasks where you need to adjust the tension frequently. It’s quick to tie and untie, making it perfect for securing fenders or rigging.

Figure eight knot

The figure eight knot is a stopper knot, used to prevent a rope from slipping out of a pulley, block, or through a hole. It’s tied by making a loop and passing the end of the rope through the loop, forming a distinctive “8” shape. This knot is often used at the end of sheets or halyards (the lines used to raise and lower sails) to keep them from pulling through blocks or jamming under load.

Why it’s essential: The figure eight knot is crucial for creating a reliable stopper that prevents lines from slipping out of hardware, which can save you from frustrating or dangerous situations.

Sheet bend

The sheet bend is used for joining two ropes, especially if they are of different thicknesses. This knot is often employed when extending lines or tying a smaller rope to a larger one. It’s secure under load, but it can be easily untied when no longer needed. Unlike a bowline, which forms a loop, the sheet bend is specifically designed for connecting two ends of rope, making it ideal for repairs or joining lines.

Why it’s essential: The sheet bend is indispensable when you need to tie two ropes together, particularly if they are different sizes, ensuring the ropes remain connected securely.

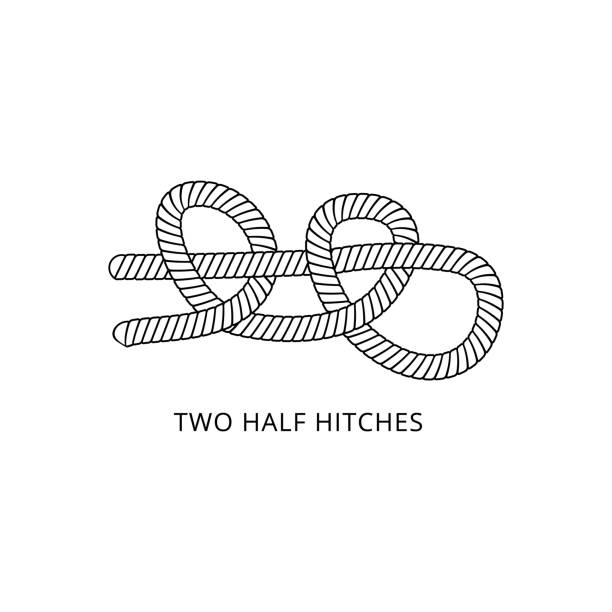

Round turn and two half hitches

This knot is another common docking knot, particularly for securing a line to a post or ring. The round turn and two half hitches involve wrapping the rope around a fixed object and then securing it with two half hitches. This knot is reliable and resistant to slipping, even under tension, making it useful for attaching mooring lines or tying off the boat.

Why it’s essential: The round turn and two half hitches provide a secure method for tying off a boat to a mooring post or dock, offering peace of mind when you need a knot that won’t budge under pressure.

The galley and beyond: Living on board a sailboat

Sailing isn’t just about navigating the open waters—life on board a sailboat brings its own unique experiences, with its own set of terms for daily life. Let’s explore some of the key terms that capture the day-to-day realities of living aboard a sailboat.

Galley

The galley is the kitchen of a sailboat, though it’s often much smaller and more compact than the kitchens you might be used to on land. Despite its size, the galley is designed to be highly functional, often with specialized appliances like gimballed stoves (which stay level even when the boat is rocking) and storage spaces that keep everything secure in rough seas. Preparing meals in the galley can be a challenge, especially when the boat is underway, but a well-organized space makes cooking on the water much easier and more enjoyable.

Personal dimension: The galley is the heart of the boat, where sailors prepare meals, make coffee, and often socialize during downtime. Managing to cook even a simple meal while the boat sways in the waves is a skill that brings a sense of accomplishment.

Berth

The berth refers to the sleeping area on a boat. Berths come in different forms—there are v-berths, located at the bow of the boat and shaped like a "V," and quarter berths, which are typically located at the rear of the boat. Some sailboats have double berths, offering enough space for two people, while others have single berths that provide a cozy, if compact, sleeping area. Sleeping on board can be a unique experience, with the gentle rocking of the boat often lulling sailors to sleep.

Personal dimension: Berths may be small, but they offer a snug retreat after a long day of sailing. Sailors often tuck themselves in with lee cloths (fabric barriers that prevent rolling out of bed) to ensure a comfortable and secure night's sleep.

Head

On a boat, the bathroom is known as the head. This term dates back to the days of old sailing ships when the toilet was located at the bow (or head) of the ship. Modern sailboats usually have small but functional heads that include a marine toilet and sometimes a shower, though space is usually tight. Managing water usage and keeping everything clean can be a challenge in such confined quarters, but learning to use the head efficiently is part of life at sea.

Personal dimension: Using the head on a sailboat requires a bit of patience and practice—flushing a marine toilet often involves pumping, and sailors must be mindful of conserving water, especially on longer voyages where fresh water supplies are limited.

Scuppers

Scuppers are drains located on the deck of a boat, designed to allow water (like rain or spray from waves) to flow overboard, keeping the deck dry and preventing water from pooling. Scuppers are essential for maintaining safety and cleanliness on board, especially during rough seas when large amounts of water can splash onto the deck. Keeping the scuppers clear and functioning properly is important for the overall maintenance of the boat.

Personal dimension: On deck, the scuppers work to ensure that water doesn’t build up, which is vital for both safety and comfort. Sailors often keep an eye on them to make sure they’re not clogged with debris, which could lead to flooding on the deck.

Cabin

The cabin is the main interior living space of the sailboat, offering shelter from the elements and a place to relax, eat, and sleep. Depending on the size of the sailboat, the cabin can range from being a simple, cozy space with a couple of berths and a galley, to a more luxurious setup with multiple sleeping areas, a dining table, and even a small lounging area. The cabin is the sailor's refuge from the wind and waves—a place to unwind, recharge, and plan the next leg of the journey.

Personal dimension: The cabin becomes the sailor’s home at sea, offering a respite from the elements. It’s where meals are shared, stories are told, and navigation plans are discussed. Even in small cabins, the sense of camaraderie and shared adventure makes the space feel warm and welcoming.

Cockpit

The cockpit is the outdoor area at the back of the boat where the helm (steering wheel or tiller) is located and where the crew often sits while sailing. This area is usually the central hub of activity during a voyage, as it’s where the boat is controlled and often where sailors spend most of their time while underway. Many sailboats have seats or benches in the cockpit, making it a comfortable spot to enjoy the view, chat with fellow crew members, and keep watch over the horizon.

Personal dimension: The cockpit is like the living room of the boat during a voyage—sailors gather here to steer, trim sails, or simply enjoy the sea breeze while keeping an eye on the boat’s course. It’s also a great place for socializing and enjoying the open water.

Knots Per Hour: The language of speed and distance at sea

When it comes to measuring speed and distance at sea, sailors don’t use the same units as those on land. Instead of miles per hour (mph) or kilometers per hour (kph), sailors use knots to measure speed and nautical miles to measure distance. These terms are deeply rooted in maritime history and remain the standard today, ensuring consistency across the global sailing community.

Let’s dive into the origin and use of these key measurements in the language of the sea.

Knots: Measuring speed at sea

A knot is the unit of speed used in navigation, representing one nautical mile per hour. But why knots? The term goes back to the days before modern technology, when sailors measured their ship’s speed using a simple yet ingenious device called the log line. This was a long rope with knots tied at regular intervals, attached to a piece of wood (the "log"). Sailors would throw the log overboard and let the line pay out behind the moving ship for a set amount of time (usually measured by an hourglass). By counting how many knots passed through their hands in that time, they could estimate the ship’s speed—hence, the term "knots" for nautical speed.

Why it’s still used: The use of knots continues today because it’s closely tied to the nautical mile, making calculations simpler and more relevant to the marine environment. In aviation, knots are also used for similar reasons, providing a consistent standard across air and sea travel.

Nautical Miles: Measuring distance at sea

A nautical mile is a unit of distance used by sailors and aviators alike, but it differs slightly from the land-based statute mile. One nautical mile is equivalent to approximately 1.15 statute miles or 1.85 kilometers. The nautical mile is derived from the Earth’s geometry, specifically the circumference of the planet. One nautical mile represents one minute of latitude (or 1/60th of a degree) along the Earth’s equator or any meridian, making it inherently linked to the planet’s spherical shape.

Why it’s still used: Nautical miles are essential for accurate navigation because they relate directly to degrees of latitude and longitude on a chart. This makes them perfect for calculating distances on the curved surface of the Earth, which is crucial when plotting courses on nautical charts.

The historical importance of knots and nautical miles

The historical use of knots and nautical miles arose from the practical need to navigate the world’s oceans efficiently and safely. Before GPS and digital chart plotters, sailors relied heavily on celestial navigation, compass bearings, and careful measurement of speed and distance. The system of knots and nautical miles allowed sailors to translate their movement into reliable progress over the globe’s surface, and because these units are tied to the Earth’s geometry, they helped navigators track their position with greater precision.

Adapting to modern technology: Today, despite the rise of advanced GPS systems and electronic tools, knots and nautical miles remain the international standard for sea travel. These units are part of the global language of maritime navigation, and they allow sailors from all over the world to communicate effectively and stay consistent with historical methods.

Conversion and practical application

Understanding how knots relate to nautical miles is key to navigating safely and efficiently. For example, if a boat is traveling at a speed of 10 knots, it will cover 10 nautical miles in one hour. This relationship between speed and distance helps sailors estimate how long it will take to reach a destination and adjust their course or sails accordingly based on weather conditions, currents, and other variables.

Example: If you’re sailing at 6 knots and your destination is 30 nautical miles away, you can estimate that it will take approximately 5 hours to reach it, assuming constant speed and conditions.

The Language of sailing safety

Safety is the cornerstone of every sailing adventure. Whether you're a novice sailor or an experienced mariner, knowing and understanding the essential safety terms is vital. These terms aren’t just words; they represent actions and equipment that could save lives in an emergency. Let's explore some of the most important safety-related terms in the world of sailing and why they are crucial for every sailor to know.

Man overboard

"Man overboard" is one of the most critical terms you’ll hear on a boat. It signifies that someone has fallen into the water and is in immediate danger. When this call is made, the crew must act quickly to locate, secure, and rescue the person in the water. The response typically includes deploying a lifebuoy or throwable flotation device, turning the boat around (using a "man overboard" maneuver), and keeping a constant eye on the person until they can be pulled back aboard.

Why It’s essential: The sooner the crew reacts to a man overboard situation, the better the chances of a successful rescue. Everyone aboard should know what to do in such a scenario and practice this drill regularly to be prepared.

MAYDAY

"MAYDAY" is the most urgent distress signal used in radio communications. When a sailor declares "MAYDAY" three times over the VHF radio, it indicates an immediate life-threatening emergency, such as a sinking vessel, a fire onboard, or a severe medical emergency. This international distress signal ensures that all nearby vessels and coast guards are alerted to the dire situation and can respond as quickly as possible.

Why it’s essential: In a critical emergency, calling "MAYDAY" can mobilize rescue efforts swiftly. Knowing when and how to use this signal correctly could be the difference between life and death at sea.

EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon)

An EPIRB is a crucial piece of emergency equipment designed to send a distress signal to rescue authorities when activated. The EPIRB transmits the vessel’s location via satellite to search and rescue teams, providing vital information about the boat's position. This device is typically used in situations where radio communication is lost or the vessel is far from land, making it a key backup for signaling help.

Why it’s essential: In the event of a major emergency such as capsizing or sinking, activating an EPIRB can lead rescuers directly to your location, even if you’re far offshore or out of radio range. It’s one of the most important pieces of safety equipment on board for long-distance sailors.

Lifelines

Lifelines are strong, often stainless steel cables that run along the sides of a sailboat's deck, designed to prevent crew members from falling overboard. They provide a physical barrier and something to hold onto when moving around the boat, especially in rough seas. Sailors often wear safety harnesses tethered to the lifelines when the conditions are particularly challenging, ensuring they stay safely attached to the boat even if they slip or are knocked over by a wave.

Why it’s essential: Lifelines are a passive but critical safety feature on any sailboat, acting as the first line of defense against falling overboard. When paired with a harness, they ensure that sailors remain secure on deck, even in difficult weather.

Life raft

In the event of a catastrophic emergency where the boat needs to be abandoned, a life raft becomes the crew’s lifeline. Modern life rafts are compact and self-inflating, designed to provide temporary shelter and survival tools like food, water, and signaling devices. They are used only as a last resort when staying aboard the sailboat is no longer safe.

Why it’s essential: Knowing where the life raft is stored, how to deploy it, and when to use it can save lives in extreme situations, such as when the boat is sinking or engulfed in fire. Practicing life raft deployment ensures a swift and organized evacuation if necessary.

Flares

Flares are visual distress signals used to attract attention to a vessel in distress. They come in different forms, such as handheld flares or aerial flares, and are often used in conjunction with other distress signals like the EPIRB. Flares are a universally recognized way to signal for help, especially at night or in foggy conditions where visibility is limited.

Why it’s essential: Flares can provide a visual cue to rescuers, helping them locate your position, especially when radio signals or EPIRBs are not immediately available. It’s important to know how to store and safely use flares, as they are typically part of any boat’s safety kit.

Float plan

A float plan is essentially a detailed itinerary left with a friend, family member, or marina staff that includes information about your route, the people on board, and expected departure and arrival times. If you fail to return or check in at the expected time, this plan gives rescuers valuable information about where to start looking.

Why it’s essential: Filing a float plan increases the chances of rescue in case of an unexpected emergency. Even if everything goes smoothly, having a float plan provides peace of mind to those on shore and ensures a quicker response in the event of an issue.

To understand sailing terminology means much more than just learning a new set of words; it means access to all that heritage and legacy in this great maritime sport, at the same time guaranteeing safety during water operations. As you learn more and more of these words and what they mean, the more adept you will become at sailing, confident, and secure. Understand that with every ounce of the sailing language learned, every journey becomes easier and less dangerous.Take a close look at these terms, practice them, and let them guide you in your maritime journeys.

Why do sailors use the terms "port" and "starboard" instead of "left" and "right"?

Sailors use "port" and "starboard" to avoid confusion. "Starboard" comes from Old English "steorbord," referring to the side where the ship was steered, typically on the right. "Port" was later adopted to refer to the left side, where ships would dock.

What are some essential sailing gear items needed for a safe trip?

Key items include non-slip deck shoes, gloves for handling ropes, life jackets, a compass, GPS for navigation, weather-appropriate clothing, and fenders to protect the boat when docking. Proper mooring lines are also essential for securing the boat.

What are the differences between a jib and a genoa sail?

The jib is a smaller sail at the front of the boat, balancing the boat and helping with steering. The genoa is larger, offering more power in light winds, but it can be harder to manage in stronger winds. Both sails complement the mainsail but excel in different wind conditions.

How do you recognize and respond to luffing?

Example: While sailing upwind, you feel the boat slow down. You look up and see your sail flapping wildly—this is luffing. Realizing you need to adjust, you trim the sail tighter to bring it back into shape, catching the wind efficiently and propelling the boat forward again.

Why is understanding windward and leeward important?

As you prepare to tack, you realize that the wind is coming from the starboard side (right side). You turn the boat to face the wind, ensuring you have a clear path to the windward side. Knowing which side is which helps you navigate effectively during maneuvers.

How do heading and course differ in a sailing scenario?

While sailing, you might find your heading is 45 degrees due to wind shifts, but your intended course is actually 60 degrees. You’ll need to adjust your sails and steering to align your heading with your desired course to reach your destination accurately.